Focus, 9-11, and Afghanistan

Chronicling an Imperial Debacle

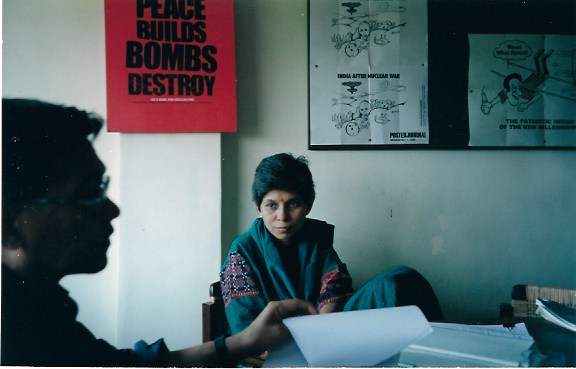

We in Focus on the Global South were, like most of the world, profoundly shocked by the horrific attack on the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001.

But when Washington’s response turned into revenge bombing and a planned invasion of Afghanistan, we warned that such a move would dissipate the wave of sympathy for the United States, lead it precisely into the trap prepared for it by Osama bin Laden, and end up with it eventually losing the war.

As we put it in “How to Lose a War,” the first essay reproduced this folio, published in October 2001, “For bin Laden, terrorism is not the end but a means to an end. And that end is something that none of Bush’s rhetoric about defending civilization through revenge bombing can compete with: a vision of Muslim Asia rid of American economic and military power, Israel, and corrupt surrogate elites, and returned to justice and Islamic sanctity.”

Read More

Indeed, Washington would likely lose this fight because it had allowed itself to be baited into a terrain where bin Laden had the strategic upper hand. As we wrote then, “September 11 was an unspeakable crime against humanity, but the US response has converted the equation in many people’s minds into a war between vision and power, righteousness and might, and, perverse as this may sound, spirit versus matter. You won’t get this from CNN and the New York Times, but Washington has stumbled into bin Laden’s preferred terrain of battle.”

The US did not see it that way, however. The administration of George W. Bush, in fact, saw September 11 as a great opportunity to reshape global geopolitics after the demise of the Soviet Union. The invasion of Afghanistan, and over a year and a half later, that of Iraq, became the cutting edge of a radical imperial effort to reconfigure the Middle East and set in stone a unipolar world.

Over the last 20 years, Focus participated in efforts to end Washington’s hegemonic project in the Middle East. It became a leading figure in global anti-war movement, beginning with its organizing an Asian parliamentary mission to Baghdad that sought to forestall the US invasion in May 2003.

As we predicted, the US became overextended but administration after administration did not want to acknowledge the failure facing it in the face.

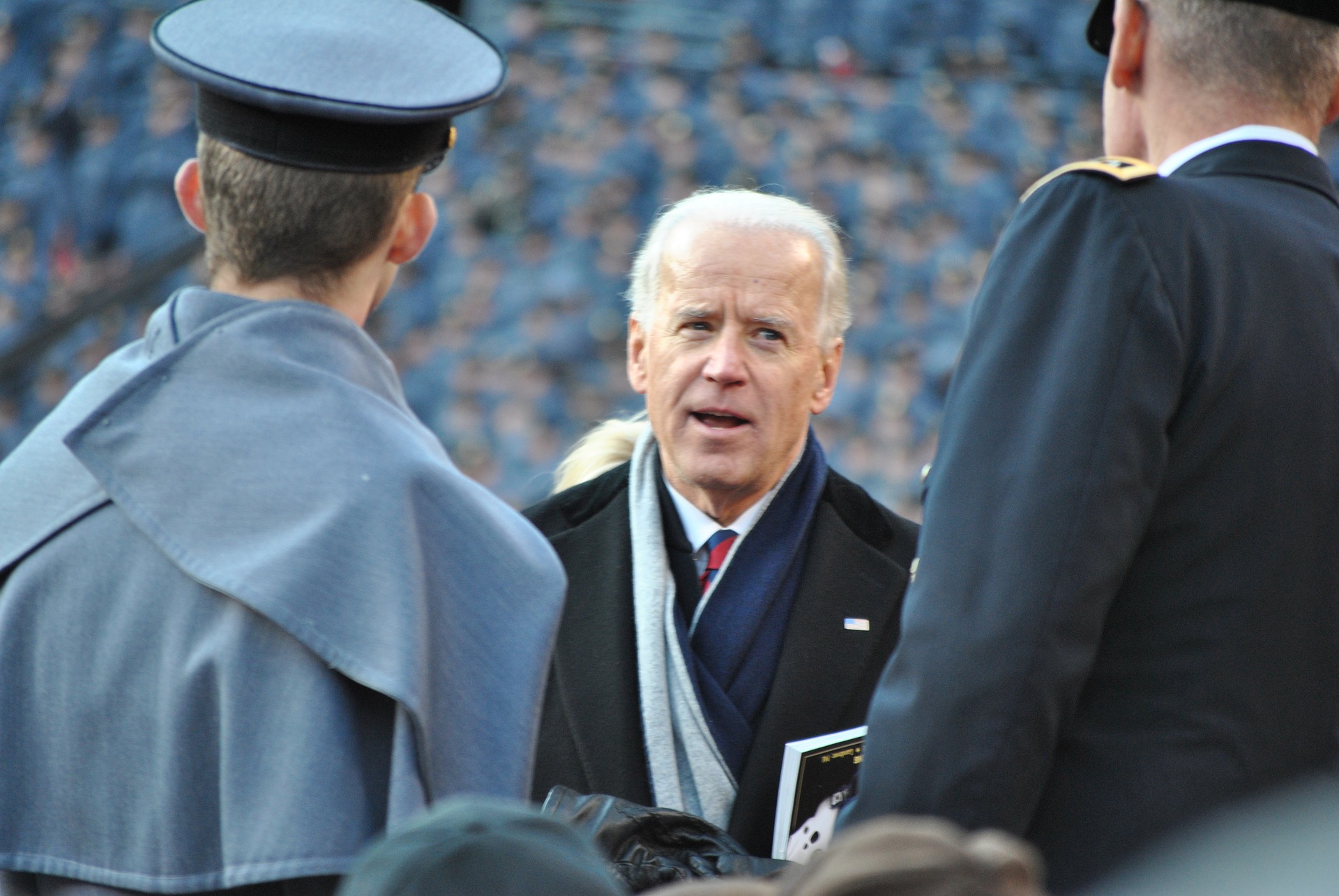

Meanwhile, clamor in the US against the the country’s involvement in endless wars forced President Trump to promise to end the US’s untenable engagement in Afghanistan but was stymied by the US military from completing it. President Biden saw the handwriting on the wall and wanted to cut and run as quickly as possible. There was no other option. He was hoping though that there would be a “decent interval” that would make US withdrawal less embarrassing.

History did not cooperate. Like the US’s earlier effort to build an ersatz nation in Vietnam that went up in smoke in few days in 1975, the American effort to create another artificial nation in Afghanistan has met a similar sudden death. Even the Taliban were probably surprised by the swiftness of the jerry-built Afghan state’s collapse. You certainly couldn’t blame them for moving quickly to fill the power vacuum. And you couldn’t expect them to make saving Washington’s face a priority.

We in Focus on the Global South are no friends of the Taliban, but we certainly are enemies of an imperial effort that created the conditions that created the Taliban and has brought so much death and destruction to the global South and especially to people in the Middle East. It is unfortunate that so many innocent Afghans that became part of the ersatz Afghan state created by the Americans may now have to suffer the consequences of being seen as allied with a doomed imperial project. We can only only hope that the Taliban will be magnanimous in their victory and let bygones be bygones with their fellow Afghans. We appeal to them not to turn back the clock, especially when it comes to women’s rights.

We are reproducing four articles that analyze the political, ideological, and economic reasons for the resounding failure of the imperial project. As noted above, the first piece, “How to Lose a War” predicted the failure of the US’s Afghan adventure. It also proposed a different, legal strategy for Washington to obtain justice for 9/11. This was, unfortunately, the road not taken.

The second essay, “Why Biden Might not be Able to Extricate the US from its Middle East Quagmire,” published in May of this year, before the final phase of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, analyzes in detail how Washington’s geopolitical aims in the Middle East went up in smoke. The third essay, “Osama Bin Laden’s ghost and the multi-trilion-dollar cost of endless war“, published in June, looks at the economic costs of America’s 20 year-long engagement in the Middle East not only in dollar terms but in terms of its losing ground to China, whose economy expanded peacefully while the US pursued war.

The fourth article, “Nation-Building: The March of an Illusion from the Philippines to Afghanistan,” published on September 8, details the vicissitudes of the political project that accompanied US military expeditions: the liberal democratic reconstruction of invaded societies. It looks closely at why this ambitious project succeeded to some degree in the Philippines and Japan but experienced crushing defeat in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

How to lose a war

From our archive: After over two weeks of Anglo-American bombardment of Afghanistan, once one gets beyond the sound and fury of American bombs and the smokescreen of CNN propaganda, it appears that in the war between the United States and Osama bin Laden, the latter is coming out ahead.

Why Biden might not be able to extricate the US from its Middle East quagmire

America’s 20-year-long war in the Middle East contributed decisively not only to degrading U.S. imperial power but also to the domestic polarization savaging the American political process at present and to the emergence of China as the new center of global capital accumulation. Ending the Afghanistan commitment, liberals and progressives hope, will provide the conditions for a fundamental reset of US foreign policy

Osama Bin Laden’s ghost and the multi-trilion-dollar cost of endless war

Twenty years of military quagmire of the Middle East has contributed to the fraying of the U.S. economy even as China has rapidly become the new center of global capital accumulation.

The first part of our assessment of Washington’s 20 years of continuous war in the Middle East focused on its military and political costs. This part will discuss the economic consequences of this misadventure. Imperial overstretch, as historian Paul Kennedy points out, is not only a result of a mismatch between military goals and military resources but of the increasing inability of the economy to generate the resources to support a political and military strategy that might have seemed manageable when it began.

Nation-building: The march of an illusion from the Philippines to Afghanistan

In one of his interviews before the Taliban walkover, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, blamed the American failure in Afghanistan on a change in Washington’s mission from anti-terrorism to “nation-building.” In his view, after the US invasion in 2001, Washington should just have held strategic sites in the country to keep terrorists off balance and not engage in an ambitious reconstruction of Afghan society.